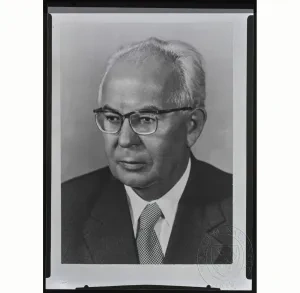

Husák, Gustáv

Husák, Gustáv (10 January 1913, Dúbravka, now part of Bratislava – 18 November 1991, Bratislava) — a Slovak and Czechoslovak Communist politician, one of the most important but also controversial Slovak politicians of the 20th century. His first wife was Magda Husáková-Lokvencová, his second the journalist Viera Husáková-Millerová. From 1933 to 1937 he studied at the Law Faculty of Comenius University in Bratislava, worked as a lawyer from 1938 to 1942 and from 1943 to 1944 was an employee of the Union of Logistics in Bratislava. A left-leaning intellectual, he was active in the Communist movement from an early age, joining the Communist Youth Union in 1929 and becoming a member of the Czechoslovak Communist Party (Komunistická strana Československa, KSČ) in 1933. As a student he was prominent amongst the young Communist intelligentsia, cooperating with the Davists (especially Vladimír Clementis), working in various left-wing youth organizations and writing articles for the Socialist press (from 1934 to 1936, he published a magazine called Arrow (Šíp) for young Communist intellectuals).

After creation of the wartime pro-Nazi Slovak Republic in March 1939, he joined an illegal cell of the Slovak Communist Party (Komunistická strana Slovenska, KSS) and was jailed several times for short periods. In summer 1943, after the arrival of Karol Šmidke from Moscow, he became one of the leaders of the illegal KSS (together with Ladislav Novomeský and Šmidke, he formed the 5th illegal committee of KSS) and in that capacity led negotiations with delegates from other anti-fascist resistance groups about a common strategy, formation of a rebel Slovak National Council (Slovenská národná rada, SNR) and plans for a nationwide uprising. As one of the leading figures in the Slovak National Uprising (Slovenské národné povstanie, SNP) and KSS, he became a member of the SNR and its presidium and was appointed Commissary for the Interior. At the congress in September 1944 in which the KSS and the Slovak Socialist Democracy party merged, he was elected as one of the two deputy chairmen of the KSS (until 1945).

After the suppression of the Slovak National Uprising, Husák went into hiding. In December 1944 he established contact with the advancing Red Army and, by January 1945, traveled to Moscow, where he reported on the uprising to KSČ leaders. At the KSS conference in Košice in late February 1945, he spoke about the action plan of the party. In March 1945, he was one of the SNR delegation which negotiated in Moscow with members of Czech political parties about the nature of the postwar Czechoslovak government and its key policies (→ Košice Government Program). Husák and the leadership of the KSS as a unit had a vision of how revolution should come to Slovakia (they reckoned on there being a fast route to a Communist monopoly on power, with more radical changes and federalization of the state), a vision which did not always correspond with the strategic planning of the Moscow, later Prague, KSČ leadership. Hence they were criticized in Prague in July 1945, which resulted in changes in leadership being made at the KSS conference in Žilina the following month. The new KSS chairman, Viliam Široký, then surrounded himself with his own followers and took the leading role in the KSS. Although Husák remained a member of the party presidium, he lost his key influence and found himself temporarily marginalized.

His resurgence began after the elections of May 1946, however, when he became Chairman of the Commissary Board (1946 – 50), 1945 Commissary for the Interior, 1945 – 46 Commissary for Transport and Public Works, 1949 – 50 Commissary – Chairman of the Slovak Office for Religious Affairs. A key figure during the political crisis of autumn 1947 in Slovakia, he was one of the most prominent members of the KSS in defeating democratic forces during the coup d’etat of February 1948 and in establishing a totalitarian regime. In 1950, however, he was accused of bourgeois nationalism and removed from office before being arrested in February 1951 and brutally interrogated. Despite facing torture, he was the only one of the accused not to admit his guilt. At a show trial in April 1954, however, his defence did not save him from being sentenced to life imprisonment for treason and sabotage. In 1960 he was granted amnesty and released from prison (from 1960 – 63 he worked in a warehouse and was later a clerk at the Building Works in Bratislava). In 1963 he was rehabilitated but in March 1964 incurred the disapproval of KSČ and KSS leadership after giving a critical address at the municipal conference of the KSS in Bratislava. From 1964 to 1968, he worked at the Institute of State and Law of the Academy of Sciences in Bratislava.

In January 1968, he returned to active politics and initially aligned himself to the democratizing reform wing of the KSČ. In April 1968, he became deputy chairman of the government of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR) and was tasked with paving the way to a Czecho-Slovak federation, becoming one of the architects of the constitutional amendment by which Czechoslovakia became a federative state on 1 January 1969. He was active in trying to bring about social reform (→ the Prague Spring), supporting Dubček’s policies and emotionally repudiating Czechoslovak occupation by Warsaw Pact armies in August 1968. He was part of the Czechoslovak delegation led by President Svoboda which negotiated in Moscow with members of the Soviet politburo on 23 to 26 August 1968. After his return, he spoke at the emergency congress of the KSS in Bratislava (26 to 28 August 1968) and changed its whole course. At the congress he was elected to the Central Committee (Ústredný výbor, ÚV) of the KSS as its first secretary as well as to the presidium of the ÚV KSČ. His political ambitions were greater, however, and by siding with the so-called realists, accepting Soviet demands and gaining support of the politburo, conservatives at home and certain reformers who believed his promises, he replaced Dubček as first secretary of the ÚV KSČ in April 1969 (general secretary from May 1971). He then took political steps to remove any traces of the reforms of spring 1968 and became the main representative of normalization, although at first he had a different vision of it, initially believing that the politics of the ‘lesser evil’ would bring fewer victims. He shifted his approach over time, however, and ended up doing what he had originally wanted to avoid by embracing a dogmatic level of pro-Soviet servility which enabled him and other representatives to retain power. Despite pressure from conservatives at home, though, he refused to hold show trials to punish people for their stance in 1968 because he was aware of their consequences. However he did allow the courts to take action against people whose activities were against the policies of the KSČ after April 1969. In May 1975 the federal assembly elected Husák as President of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. He was the only Slovak to hold this position during the state's existence.

The political changes and reforms which followed the appointment of Mikhail Gorbachev as general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1985) were not enough to force Husák to address the growing crisis in Czechoslovak society and implement reforms of his own. He became increasingly isolated and lost his influence on political developments in Czechoslovakia. In December 1987 he resigned as general secretary of the ÚV KSČ (Miloš Jakeš replaced him) but remained a member of the presidium. The collapse of the Communist regime in Czechoslovakia at the end of November 1989 (→ Velvet Revolution), however, forced him to abdicate as president on 10 December 1989 and leave politics for good.